Rehabilitate or Punish? The Question Facing Hundreds of Prisons Across the Country

How does a society deal with people who break that society’s agreed-upon codes of conduct? For millennia, humans have used a model in which lawbreakers are sequestered together in institutions designed for that purpose. Such an approach allows the rest of society to function normally without the threat of dangerous people who don’t conform to society’s moral codes.

As they advanced, societies sought to add an additional function to the institutions (prisons) that held dangerous people away from others. The prisons were to rehabilitate offenders so that when offenders returned to society after serving a sentence, they wouldn’t simply go back to breaking the law.

Unfortunately, while prisons have gotten quite good at holding lawbreakers away from society, they have not yet succeeded in reforming those held under their charge, as evidenced by the 44% to 89% recidivism rate among prisoners in the United States.1

Prisons Aren’t Supposed to Be Fun But…

Prisons are not supposed to be fun, but recent decades have seen a spike in the U.S. recidivism rate as strict mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines, budget shortfalls, and a punitive philosophy of corrections have made modern-day American prisons an unpleasant and unproductive place to be.2

Prisons didn’t always have a punishment-first model. Until the mid-1970s, while prison conditions weren’t always great, the intent to focus on rehabilitation had a strong presence in prisons. Many U.S. incarceration facilities encouraged and helped prisoners develop occupational skills and resolve psychological problems like substance abuse or anger problems that might interfere with their reintegration into society. In fact, rehabilitation was so central to incarceration that many court sentences mandated a slew of rehabilitative programs that inmates had to complete to be released.

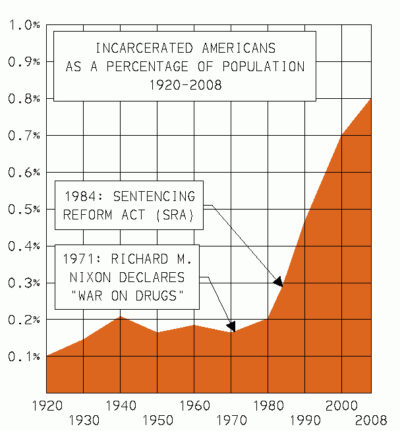

Sadly, occurring alongside the (now failed) War on Drugs from the 1970s, a “tough on crime” approach emerged, modeled on the idea that if prison is brutal enough, it will act as a deterrent to lawbreaking. This turn toward punishment as a main focus has not worked, as the U.S. now incarcerates more people per capita and as a percentage than any country in the world. Since 1970, the U.S. prison population has increased by 500%, far outpacing the population growth. The U.S. has just 5% of the world’s population, yet it holds 20% of the world’s prison population.3

Prisons Can Be Harmful If They Don’t Seek to Reform the Offender

There’s no shortage of literature and scientific data outlining a prison sentence’s harmful effects. One such study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, showed how simply replicating prison conditions in an experiment produced harmful outcomes for those involved. “How we went about testing these questions and what we found may astound you,” wrote Professor Philip G. Zimbardo, co-author of the experiment and the study that followed it. “Our planned two-week investigation into the psychology of prison life had to be ended after only six days because of what the situation was doing to the college students who participated. In only a few days, our guards became sadistic, and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.”4

“How we went about testing these questions and what we found may astound you…”

Prisons can shape behavior, which goes both ways when punitive, cruel, and unhelpful prisons shape behavior to the detriment of prisoners and prison workers. Conversely, when properly implemented, work programs, education courses, life skills training, reentry programs, and job preparation courses can facilitate an effective, optimistic transition back into the free world.

The More Severe the Prison, the More Harmful the Effect on Inmates

Not all prisons are the same. Some scholars have observed that the more punitive a prison is, the more likely it is to produce negative outcomes for inmates there. For example, high-security “supermax” prisons (which have become increasingly common in the 21st century) can harm inmates by frequently placing them in solitary confinement for 22 to 24 hours a day, sometimes for years at a time.

Research shows inmates in supermax prisons experience extremely high levels of anxiety and other negative emotions associated with confinement. When released (they’re often released without any “decompression” period in lower-security facilities), they have few of the social or occupational skills necessary to succeed in the outside world, thus increasing their chances for recidivism.

Criminon Provides Real Tools for Reform

Criminon, a word that means “without crime,” is a nonprofit organization dedicated to criminal reform and rehabilitation. Criminon helps offenders improve their lives through services that improve self-respect, communication, and relationship skills while breaking destructive habits.

Criminon helps inmates prepare for life outside of prison by giving them the tools they need to overcome the underlying reasons why they committed crimes in the first place. Through life skills courses and on-site programs that teach basic skills and strategies for responsible, moral living, Criminon helps offenders regain their self-respect and personal integrity, enabling them to return to society as productive citizens. Criminon and organizations like it are incredibly needed to shift prisons away from places of punishment to places of reform and rehabilitation.

Sources:

- DOJ. “Punishment vs. Rehabilitation: A Proposal for Revising Sentencing Practices.” United States Department of Justice, 1991. ojp.gov

- APA. “Rehabilitate or Punish?” American Psychological Association, 2003. apa.org

- ACLU. “Mass Incarceration.” American Civil Liberties Union, 2024. aclu.org

- SPE. “The Stanford Prison Experiment: A Simulation Study on the Psychology of Imprisonment.” Stanford Prison Experiment, 2024. prisonexp.org